Scientists at the Marine Biological Association have used a pioneering technological approach in individual diatom cells to uncover how these microscopic ocean organisms rapidly adjust their carbon uptake strategies to cope with changing conditions in the ocean. This discovery identifies a previously unknown flexibility that helps diatoms maintain photosynthesis and sustain marine ecosystems, even as the ocean changes.

The research

Diatoms are among the ocean’s most important primary producers, forming the base of marine food webs and playing a major role in global carbon cycling. Although there is plenty of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in seawater, only a tiny fraction is available as carbon dioxide (CO2). Diatoms can employ two additional pathways to acquire sufficient carbon for photosynthesis:

- External carbonic anhydrase (eCA): an enzyme that converts bicarbonate into CO₂ for photosynthesis.

- Direct bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) uptake: an energy‑intensive process.

However, it was unclear how these pathways interact when conditions change, due to shifts in light or CO₂ levels. These processes are also essential for understanding how diatoms may respond to future changes in CO2 availability.

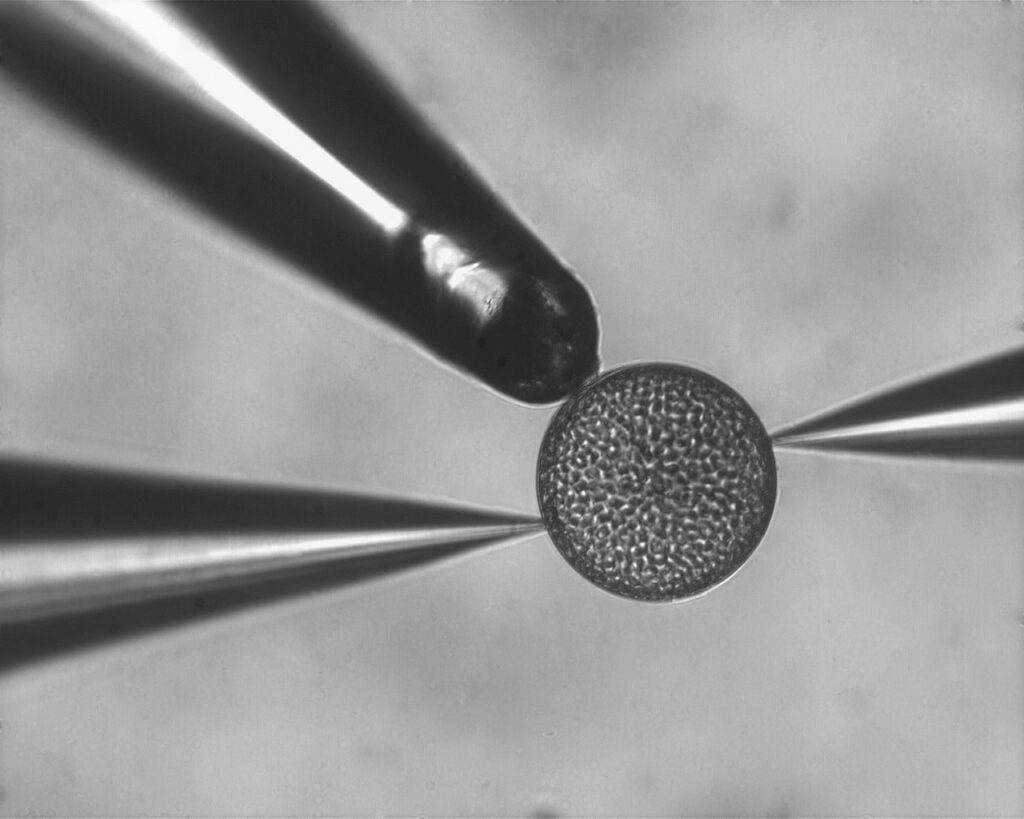

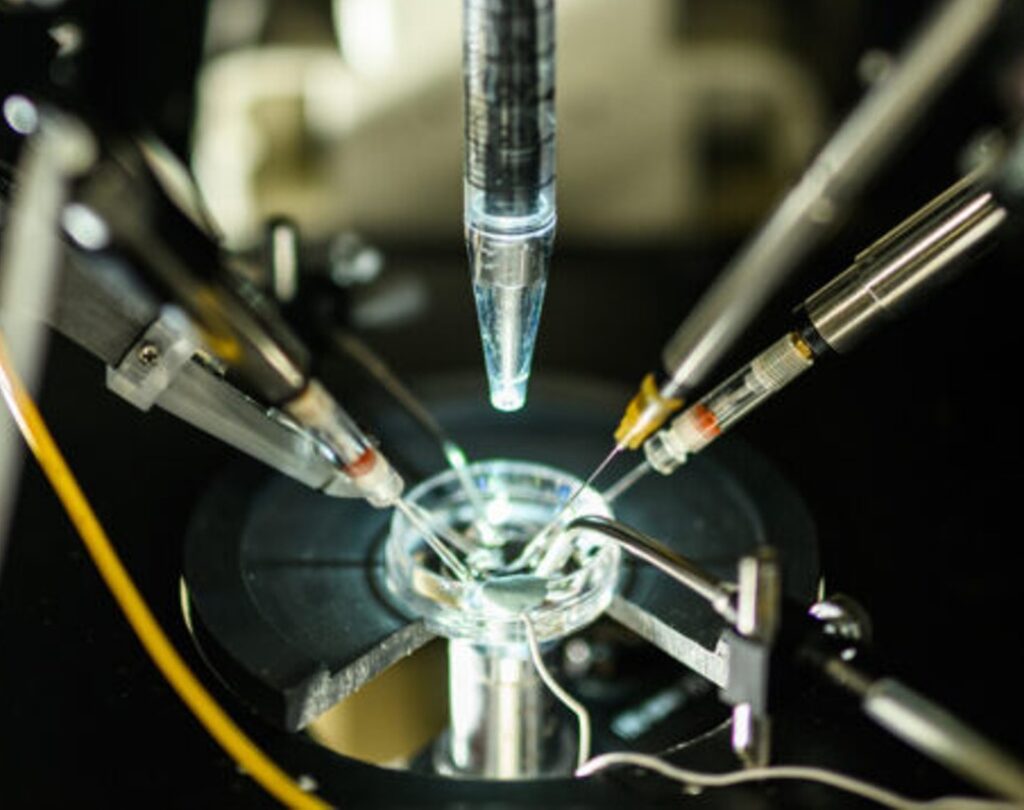

Using pioneering single‑cell microelectrode technology, the MBA team measured real‑time changes in the chemical microenvironment (the ‘phycosphere’) around individual diatom cells, positioning ultra‑fine pH and carbonate sensors directly at the cell surface to capture rapid responses as light and chemistry changed.

Microelectrodes positioned at the cell surface of the large diatom, Coscinodiscus granii. The image was acquired on a Nikon Diaphot inverted light microscope. c. Marine Biological Association

The MBA team’s use of single‑cell sensors marks a breakthrough in marine science. This direct, cell‑scale vantage point reveals physiological processes that bulk studies cannot detect. By measuring photosynthesis in single cells, the approach revealed that diatoms can switch carbon‑uptake modes within minutes, activating bicarbonate transport when eCA is inhibited or when CO₂ becomes scarce.

Historically, researchers have studied diatoms by measuring carbon uptake in large cultures containing millions of cells. This ‘bulk’ method provides an average of all cellular activities, showing that diatoms take up both CO₂ and bicarbonate. However, it misses the nuances of individual cell behaviour and adaptability. The single cell approach provides deeper insight into the survival strategies of diatoms in fluctuating environments, uncovering a more accurate and dynamic picture of how diatoms respond to environmental changes.

Microelectrodes are placed onto the surface of single diatom cells, allowing scientists to observe responses at the individual cell level and changes in real time. c. Marine Biological Association.

Dr Glen Wheeler, Senior Research Fellow at the MBA and co‑author of the study, Dynamic changes in phycosphere carbonate chemistry reveal rapid modulation of carbon uptake in single diatom cells, says:

“The novel single cell approach involves using tiny microelectrodes placed directly at the surface of individual diatom cells to measure pH and carbonate ion concentrations. This allowed us to observe real-time changes and responses at the single-cell level, revealing that a cell can rapidly switch between different modes of carbon uptake. This flexibility and adaptability are not visible when only bulk averages are considered.

“The difference is like studying a population of people: if you only look at the average of their activities, you miss the unique behaviours and processes of each individual. Similarly, bulk studies of diatoms reveal only the sum of their activities, not the specific, flexible responses of single cells.”

This focus on individual cells allowed the researchers to understand the true adaptability and survival mechanisms of these microscopic organisms, which are essential for thriving in diverse and rapidly changing environments.

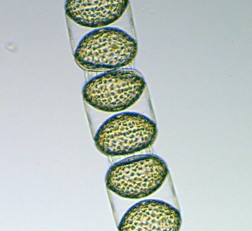

Stephanopyxis palmeriana, a species of centric diatom found in marine environments. c. Marine Biological Association

Why this discovery matters

The dynamic flexibility uncovered by this research is critical for ocean health. Diatoms often dominate in regions where light, turbulence, and nutrients fluctuate, from estuaries to the brine channels of sea ice. Their survival in these dynamic environments depends on the capacity to keep photosynthesising despite rapid changes in water chemistry and light. Their ability to rapidly adjust carbon uptake ensures continued carbon fixation, the process that underpins marine food webs and helps to regulate Earth’s climate.

Looking ahead

These new insights help scientists to interpret past and future experiments on phytoplankton grown under different CO₂ levels, improving predictions of how diatom communities will respond as the oceans continue to change.

“These findings help us to understand how these organisms will respond to changes in global CO₂ and will allow us to better interpret and understand previous experiments,” says Dr Wheeler. “The results show that diatoms are far more flexible than we realised. This helps them thrive in dynamic environments and highlights their essential role in sustaining marine ecosystems.”

The method can be applied across phytoplankton and even to seaweeds and seagrass, opening new avenues to understand how different marine producers respond to changing CO₂.

About the study

The research was conducted by scientists at the Marine Biological Association and partners, funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and the Human Frontier Science Program.

Read the full paper here.